WHEN I joined Watford from Walsall, I had gone from being a big fish in a small pond to a tadpole in a lake.

The idea was that I was going to be the main man, but that changed because the team was doing well without me. The more I had to wait, the worse it got.

I was still living in Chelmsley Wood in Birmingham and still going out with all my mates, and now I had all this money and I wasn’t playing.

I could get drunk four or five nights a week and still be fit enough to give everything for ten or 15 minutes at the end of a game.

I was going straight from a nightclub in Birmingham to catch the 4.30am train to Watford Junction, sleeping in my car for a couple of hours at the Watford training ground before I went out to play football.

I was running in crazy circles. Once a month we’d go to a different city. I got glassed in the back of the head during a fight in a club in Leeds one Tuesday night and my best mate, Marc Williams, drove me to Watford training so I could be there on time on Wednesday morning.

I went straight to the showers and washed the blood out of my hair.

I didn’t want to explain to the manager, Malky Mackay, what had happened so when we were having a practice match I went up for a header with Tommy Aldred, who was a big defender.

I engineered it so he ran into the back of me and I went down holding my head. The physios had a look, saw the gash and I got it stitched up with no one any the wiser.

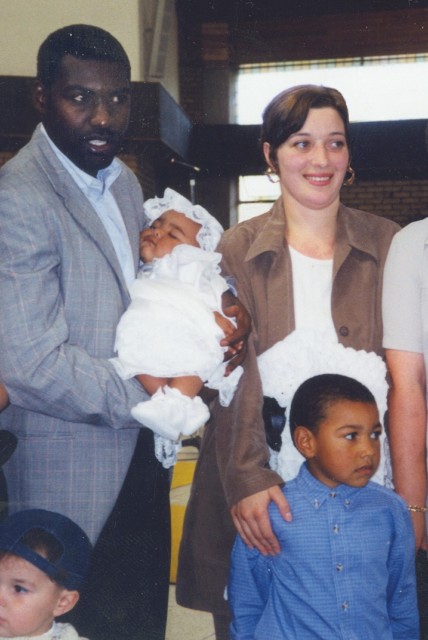

When my dad, Paul Anthony Burke, was diagnosed with terminal cancer, I found it hard to deal with.

ANXIOUS, SAD AND ANGRY

So I tried to forget about it. I was given Dad’s diagnosis on the Monday and later in the week it was the anniversary of my Great-Nan passing away.

Then there was the fact it was my best mate’s birthday. So that was a great excuse to go out and get wasted.

Associating drink with a good time is cool, but drinking when you are anxious, sad and angry exacerbates those feelings and fuels them.

That night we went out — February 29, 2012 — was the night after I found out about my dad’s condition and the rush of emotions pushed me right up to that limit then over the edge.

There were probably 12 of us in total. My brother Ellis was out too, with some of his friends.

We parked close to Broad Street, in Birmingham, hit a couple of bars and then the Rococo club. We left the club at 3am, obviously drunk.

I was a little way up ahead but when some of the lads passed the entrance to a club called Bliss there was a bit of a kerfuffle. There was trouble inside Bliss and the bouncer knew a lot of people were about to be kicked out so wanted to clear the area.

The bouncer pushed a couple of my mates and they took exception. There was an argument, then the lads who were causing trouble in Bliss got kicked out and started fighting with my mates. All of a sudden there was a brawl going on.

Someone came up to me and said something about my brother. They said he was in a fight.

There were three different groups of people fighting.

All I thought was, ‘my brother’s in there somewhere’, and I lost my head. I ran into the middle of it, hitting anything that moved that was in the way. I was like someone clearing out a ruck in a rugby match.

I hit one lad and he fell against the side of a taxi. This lad — he was a student — went down but as I turned to start fighting again, I felt him tugging at my leg. If you know fighting, if someone’s grabbing at you there’s a chance he’s got a weapon. So I kicked him in the head. I just put him out.

That’s the only part I don’t like talking about. The guy could have died, because I am a powerful guy. I didn’t think about my actions. When the police showed me the video the next day I couldn’t watch.

Then we ran up the road. I knew the police were coming. I could hear sirens. I thought I had got away. Then I realised my brother wasn’t with me.

It was his first time out on the town and he didn’t know where he was going. I turned round and saw him running straight down Broad Street — exactly the place you are going to get caught.

Until that moment I thought I’d try and get away. I knew where the cars were parked so I was going to go back there and lie down in the back seat and throw something over myself to conceal my presence.

But when I saw Ellis running up Broad Street I knew I had to turn around and get him. I couldn’t go home without him. Mum would never have forgiven me.

So I caught up with him, grabbed him and threw him back the way we were supposed to go. We’d only gone a few yards when the police arrived and jumped on us.

We were thrown into the back of a police van and taken to a small jail at the back of Broad Street, the Steelhouse Lane lock-up, where the mugshots of the notorious Peaky Blinders were taken in the old days.

We buried my dad on a Friday. The following Monday I went to jail. It’s not what you usually envisage when you think of a long weekend.

But they were two seminal events in my life, two moments that have shaped the years that have passed since and, in their different ways, set me on the long path to the redemption I’m still trying to achieve.

I guess altercations are not that uncommon at funerals, when people are emotional. It wasn’t really a surprise that there was a fight at my dad’s funeral. Most of his life had been accompanied by fighting. So why not his death too?

The wake was in the Irish Centre in Solihull. I was talking with friends late in the evening and saw my sister, who was 14, talking to a couple of geezers who had just walked in. I watched them for a minute and saw her burst into tears and run out of the room.

They hadn’t been invited and one of them said something inappropriate to my sister about my dad.

A few minutes later someone came up to me and told me to follow him and not to ask any questions.

We found the geezer at the bar carrying on as if nothing happened and we confronted him. We threw him outside and the people at the Irish Centre suggested fairly firmly that we should call it a night.

And so, on the morning of June 25, 2012, I walked through the entrance of Birmingham Crown Court to hear my sentence. The prosecutor told the court I punched a student called Nathan Parton, who fell to the ground and that I had kicked another student, Liam Baister, in the head while he was on the floor.

It was the first time I had heard the names of the victims. Mr Parton lost consciousness briefly and suff- ered a broken jaw, while Mr Baister had to have 16 internal stitches put into his lip as well as four external ones.

BROKEN JAW

They played the footage. The judge saw the kick and heard I was charged with affray. He said he was surprised that I had not been charged with grievous bodily harm.

He looked annoyed. He said he thought the charge should be upgraded but, because I had already pleaded guilty to affray, I think the law took that out of his hands.

Then he read out the sentence. It was ten months in jail. I didn’t feel angry or resentful, lucky or unlucky, or ashamed or defiant. I just felt numb.

Winson Green prison is an imposing place, a proper old Victorian jail.

After three or four days I was allowed to go to the gym. One of my jobs was cleaning the equipment.

I ran into two lads there who I knew only as The Twins, two fellas I’d met on the outside through my dad. They told me to come with them, because there was someone who wanted to speak to me.

They took me to this bloke, who was a huge guy. “You’re a f***ing idiot, aren’t you?” he said. “Yeah, probably.”

He said if it wasn’t for the fact I was Burkey’s son he would have chinned me as soon as he saw me. I talked to them for about 45 minutes.

They said: “Us, this is all we know, crime, all that s. You are getting paid to play football, which is all of our dreams and all our kids’ dreams and yet you’re in here with us, you f***ing idiot.”

It was a dressing down dished out by people I respected so I didn’t answer back. Every word sank in and hit home.

I know it would be easy to go back to the way I was before, to court trouble, to flirt with disaster. I fight that fight every day, to avoid slipping back into the old habits.

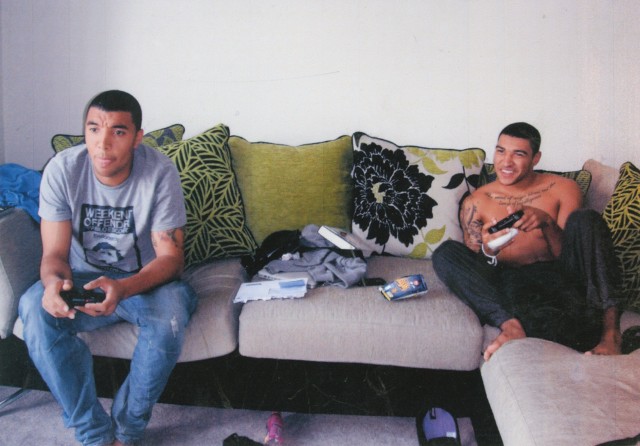

I am the happiest I’ve been in my adult life now. My kids, Myles, 12, Isla, seven, Amelia, six, and Clay, 18 months, are happy, the missus, Alisha, is fantastic and I am getting into that space now where everybody is starting to understand where I am and I am starting to have conversations that allow people in.

I fight not to revert to my old traits. It is a dangerous slope, that, because it only takes one night to fall. It takes the rest of your life to be strong.

- Troy Deeney – Redemption: My Story is out on Thursday (Hamlyn, £20, octopusbooks.co.uk).

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.sportingexcitement.com/football/premier-league/man-utd-star-bruno-fernandes-apologises-to-fans-for-shocking-missed-penalty-vs-villa-saying-today-i-failed